The Libyan conflict has been ongoing for a decade. The impact on Libya’s oil production has been significant. Whether the new transitory government and shift to democracy will increase and stabilise Libya’s oil production in the short-term is yet to be determined.

However, as the country has the largest proven oil reserves in Africa and the 9th largest in the world, it is clear Libya’s approximately 48.8 billion barrels will eventually flow and this could be a potential windfall for the European oil market. Libyan oil provides the country its clearest path to economic prosperity. But with so many parties, domestic and foreign, completing for access and domination it remains to be seen whether Libya’s citizens will reap any rewards once oil production is back up to its pre-conflict levels. Additionally, there is risk that competition for control of Libya’s oil field may only fuel the ongoing conflict.

Prior to the toppling of the Gaddafi regime, Libya was able to produce 1.7 million bpd. When the conflict began in 2011, Libya was initially stable enough to continue to pump oil, however production slowly began to decrease. In 2012, Libyan oil amounted to ten percent of all European oil imports. However, increasing tensions between Libya’s rival administrations the GNA and LNA, and rival militias such as The Petroleum Facilities Guard (who had previously been responsible for guarding Libya’s critical energy infrastructure), led to the destruction of much of Libya’s energy infrastructure. By 2015 the only infrastructure operating was in the Sarir cluster field in the east, the Sharifs port a Tobruk and a handful of platforms of the coast of Tripoli.

The GNA and LNA are fighting for control of the country’s oil reserves. The National Oil Corporation (NOC) is state-owned and therefore under the control of the GNA. The NOC is the only entity permitted to manage and sell Libyan oil. However, the LNA have attempted to break this monopoly, using tactics such as the capturing of Libya’s ‘oil crescent’. Several European oil companies including Total, Repsol S.A., and Eni, have been active in Libya for decades and their operations have been severely impacted by the conflict. Eni is the largest foreign oil producer in Libya, however, it is facing increasing competition from Total who are expanding across the country.

Libyan oil offers a strategic advantage to the European Union; following the war in Ukraine, the block has been increasingly concerned about reducing its dependence on Russian oil. A conflict-free Libya could produce enough oil to lessen Europe’s dependence on Russian oil. Yet, the European Union has largely ignored the Libyan conflict since the Arab Spring in 2011. However, with the recent involvement of Russia and Turkey backing Libya’s rival administrations, Europe has suddenly awoken to the implications of destabilisation in North Africa.

And while Europe has now signified its collective interests in accessing Libyan oil and maintaining regional security, European countries are not unified in their position on the political leadership in the country with France and Russia backing the LNA and Italy and Turkey backing the GNA. In fact, as European states have entered the Libyan conflict to pursue their own and often divergent interests, the Libyan situation has only become more complex, with the conflict becoming a proxy for disputes between foreign powers. Russia’s interest in Libya threaten the interests of the EU, however, the greater threat is arguably the unwillingness of member states, particularly France and Italy, to collectivise their interests for the benefit of the block.

Europe, and particularly the European Union’s collective lack of interest, has left the continent looking weak and peripheral in the context of the Libyan conflict. Tarek Megerisi of the European Council on Foreign Relations has said “it’s not that Europe is incapable, it seems that it’s unwilling” – Libya is effectively in Europe’s backyard, stabilising the country and more broadly North Africa should be considered an EU priority. Unwillingness to act sets a dangerous precedent when the Libyan conflict encompasses many geopolitical concerns – including migration, security and counterterrorism, that the block profess to be so concerned about.

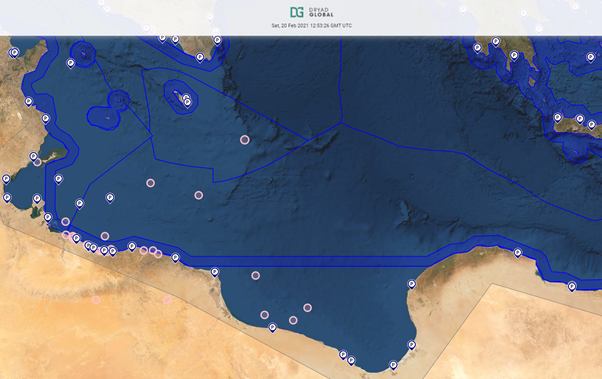

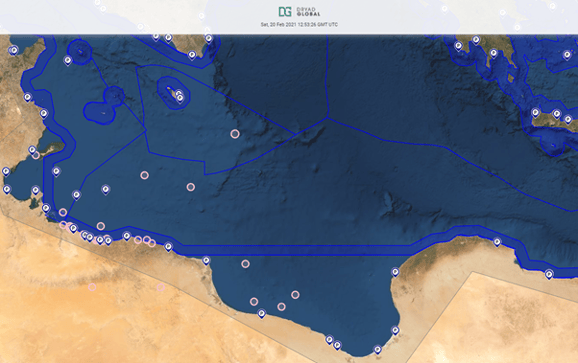

Download a complimentary copy of our latest weekly Libya security report. Read more original content from Dryad Global's analysts in our Annual Report.

Related Posts

As New Libyan Authority Takes Shape, Challenges..

The head of Libya’s new presidency council is due soon in the capital to begin work on a..

Strike ends at Marsa al Hariga

Libya's Marsa al Hariga terminal has reopened.

NOC declares force majeure on Zawiyah and..

Libya's National Oil Corp (NOC) has declared force majeure on crude exports from the Zawia and..