12 min read

Will the Gulf of Guinea Ever be Free of Piracy?

By: Unicorn Riot on July 24, 2023 at 8:00 AM

Maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea continues to pose a serious threat to the safety of crew members as well as the integrity of international trade. Despite considerable progress made through initiatives like Nigeria’s Deep Blue Project, challenges persist. Corruption, illegal fishing, political instability, and a high unemployment rate contribute to the ongoing problem.

The Gulf of Guinea and its neighboring nations are vital parts of global trade. The Gulf of Guinea is a colossal 2.35 million km² part of the Atlantic Ocean, sourced by the Niger River and the Volta River in Nigeria and Ghana, respectively. The Gulf is just off Western Africa, and its waters stretch from Liberia in the west all the way south-east to Angola. Its 6,000 kilometers of coastline encompasses seventeen independent nations and a colossal GDP of $886.3 billion as of 2021. With Somalia’s similar piracy issues far in the rearview mirror, the ongoing crisis begs the question as to why the same hasn’t happened in the Gulf, or if it ever will.

This is an analysis of the narrative at hand, why it continues, and what could possibly be done to protect those who continue to brave the Gulf.

Recent Developments

On March 25, 2023 at almost midnight, a Danish-owned tanker flying the Liberian flag and supplying fuel to other nearby ships was attacked in the Gulf of Guinea, 138 nautical miles west of the port city of Pointe-Noire. Monjasa, the company that owns the oil tanker explained that for their safety “the entire crew put themselves in the [hold] of the ship.” According to the Congolese authorities, it was three armed men who had immobilized the boat.

Five days after the initial attack, six members of the crew were kidnapped by the pirates as they abandoned the tanker. These six crew members endured a staggering five weeks of captivity before being rescued in an undisclosed location in Nigeria. The CEO of the Danish company Monjasa, Anders Ostergaard, confirmed after the crew’s rescue that “all recovered crew members are in a relatively good health condition given the difficult circumstances they have been under in the last more than five weeks.” The crew were given medical checks and have since returned to their homes and been repatriated with their families. However, the event left the Danish Shipowners Association declaring that “piracy problems off the west coast of Africa are far from being resolved.”

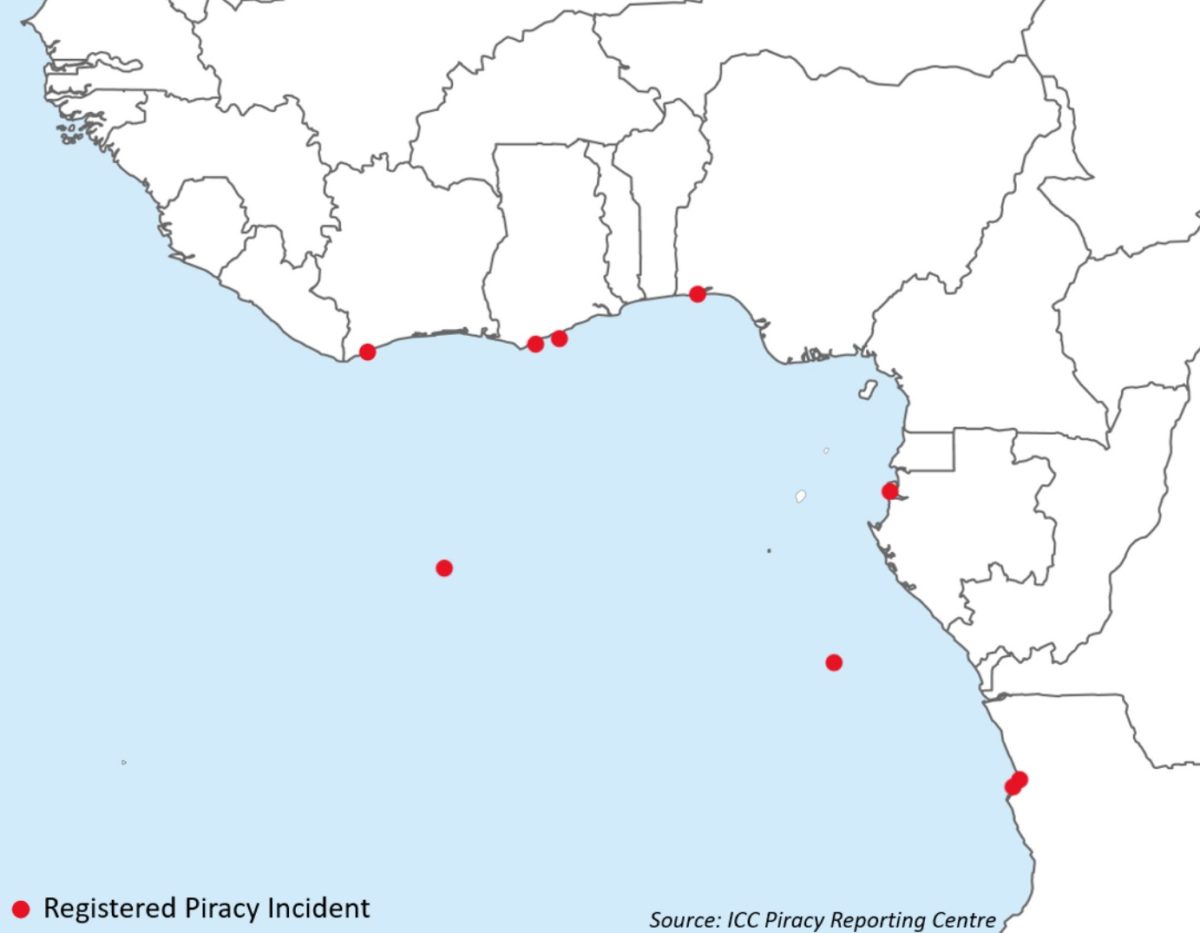

According to the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre, there have been nine incidents in 2023 of varyingly serious pirate attacks in the Gulf of Guinea. One of these events details 12 heavily armed men successfully hijacking a tanker 300 nautical miles southwest of Abidjan in the Ivory Coast. The tanker’s crew was restrained with cable ties and had their equipment destroyed during the hijacking.

Although there continues to be a consistent flow of reports from the Gulf of Guinea of violent incidents this year, there have been huge strides made to extinguish piracy in the Gulf since 2020.

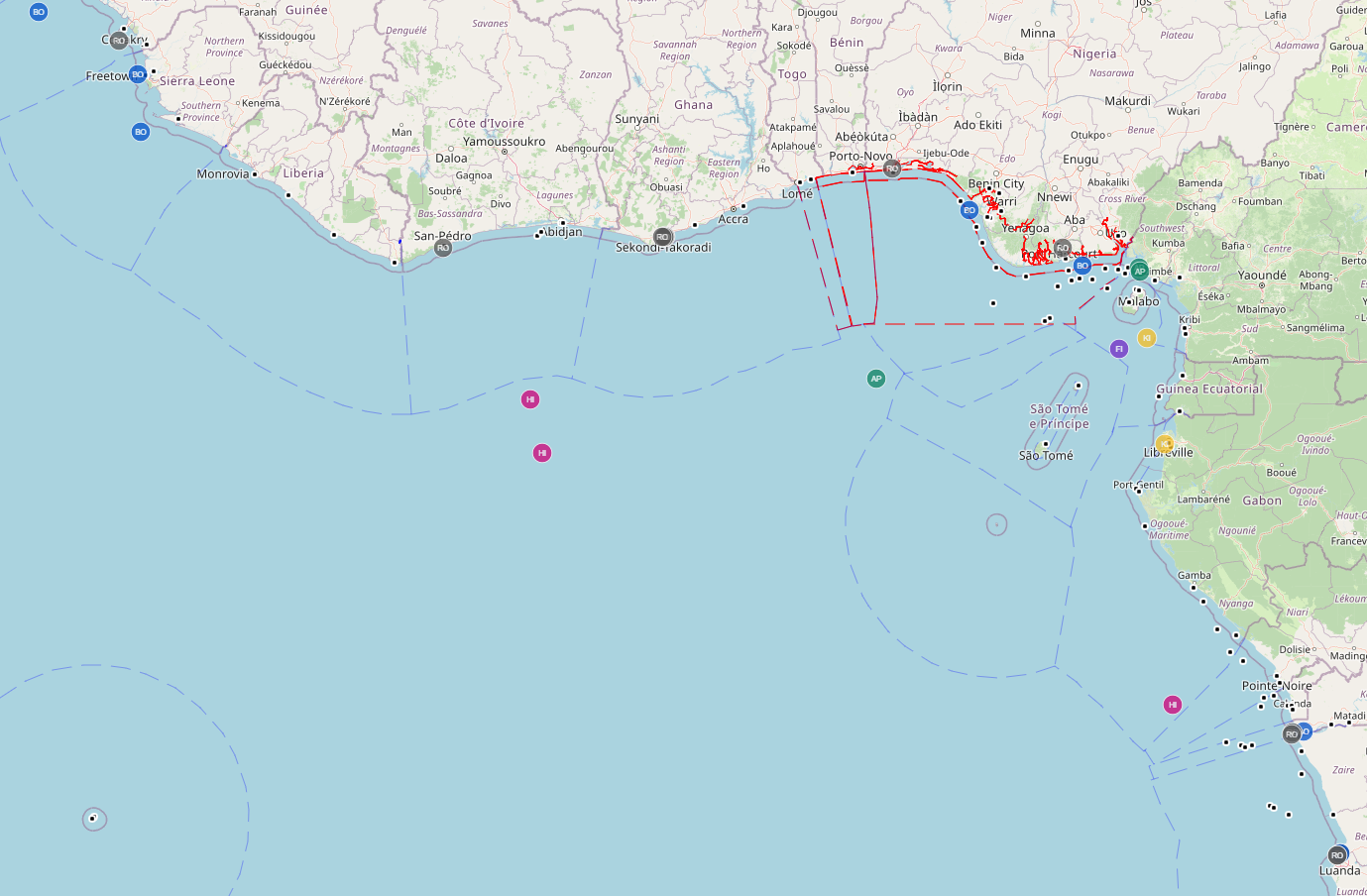

Map of piracy incidents in the Gulf of Guinea as of June 20, 2023.

Progress Since 2022

A tally of nine incidents this year alone is concerning; however, it is a far cry from how prevalent piracy was in the Gulf only a few years ago.

Over the last 15 years, the Gulf of Guinea has lapsed the Gulf of Aden and Horn of Africa’s incidents massively. The numbers were especially concerning between 2018 and 2021. At least 121 seafarers were abducted in 2019 alone in the Gulf, and the following year, 130 of the 135 global maritime kidnappings occurred there. During this period, the number of kidnappings was unprecedented and not seen anywhere near this volume elsewhere in the world. In addition to this, during the first four months of 2021, 40 crew members were kidnapped worldwide, all in the Gulf.

The attacks were even more ambitious and daring. Over 390 kilometers south of Cotonou, Benin, 15 members of a Maltese chemical tanker were abducted. The sheer range with which the pirates were able to attack at this time displays not only profound confidence but also that they were better equipped to achieve more difficult hijackings. During these attacks, seafarers were frequently injured and, in some cases, even killed.

The Gulf of Guinea has always been a linchpin of trade between Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Due to this, there were attempts in the early 2000s to curb piracy; however, most of these early methods were relatively ineffective. Likely the most notable is the June 2013 Yaoundé Architecture Agreement, in which 25 states and leaders of the ‘Economic Community of West African States’, met in Yaoundé, Cameroon, to strategize. It aimed to create a common regional strategy to target illicit activity in the seas of the Gulf; however, the self-interest, long-held grievances, and economic ambitions of the 25 states made the agreement somewhat unfruitful despite some measured progress.

Another early deterrent was the fact that European powers held an interest in the Gulf. Countries like France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, the UK, and the United States all conducted naval missions, thus increasing local security. These nations also provided ships and equipment to some coastal states. However, the interest was likely to secure economic prosperity for their own fishing and oil companies as well as simply protect trade flowing through the Gulf.

The most effective countermeasure to date has been former President Muhammadu Buhari’s announcement of the formation of ‘The Integrated National Security and Waterways Protection Infrastructure of the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency’ (NIMASA), far more commonly known as the Deep Blue Project. It was announced in June 2021 and allowed a combination of Nigeria’s navy, army, air force, and police to cooperate to counter piracy. From 2020 to 2021, attacks decreased by an impressive 60%.

As well as this, a further strategy was announced by Nigeria and stakeholders in July 2022. In May, a United Nations Security Council member labeled the Gulf as the world’s piracy hotspot despite recent success. And so, the countermeasures already in effect were bolstered further by international figures.

A Nigerian Navy spokesperson stated, “The Nigerian Navy plays a vital role in ensuring maritime security. Collaborating with national as well as international stakeholders is most important, and this joint strategy demonstrates the good that can be achieved by working together.” This strategy was formulated only a month after Russian gas exports had been halved due to Western sanctions in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Due to the Gulf of Guinea being home to around 6% of the world’s natural gas reserves, it’s likely this was simply a pragmatic economic tactic to ensure the security of gas supplies, given the international circumstances.

Given all these countermeasures and their increasing success, piracy in the region is as low as it’s been since 2018. However, many men continue to risk their lives and liberties to pursue this way of life. This is because it is a far more deep-rooted issue than simple criminal opportunism.

The Conditions Causing Piracy

In Somalia, piracy became rampant after a complete state collapse. In the Gulf of Guinea, however, there are a multitude of causes that foster piracy. Although there are multiple, they intersect considerably. One common element behind them is the lack of development in many of these Gulf states, which contributes to weak jurisdictional and legal systems. As a Chatham House report describes it, states tolerate a highly complex ‘criminal web’ that encompasses “foreign oil trades, shippers, bankers, refiners, high-level politicians, and military officials.”

Corruption plays a significant role in exacerbating the issue. Billions of dollars appear to have disappeared into the foreign bank accounts of corrupt politicians. One particular area where corruption thrives is in the processes related to oil production and exportation in the Niger Delta. While it is challenging to establish direct connections between these officials and piracy, corruption within the Nigerian Navy is more visible.

Another issue is the highly common practice of ‘oil bunkering’, meaning to steal, divert, or smuggle oil without authorization. Oil bunkering is widespread in the Navy, and a recent study from 2023 estimates that Nigeria’s economy has suffered a loss of 2.184 trillion naira due to bunkering, as well as having damaged local communities economically and posed environmental challenges.

Oil accounts for 9% of GDP and 90% of exports in Nigeria, creating a substantial incentive for pirates to siphon some of the profits when it’s opportune. Fuel and oil theft results in between a 6% and 10% loss in the country’s output. Considering the huge revenue oil brings to its nations through exports, it is likely many young people feel ostracized for barely getting by in the legal economy, and therefore indulge in this criminal enterprise.

Illegal fishing is another gateway for piracy, and it’s an issue that arises when states are unable to maintain control of their territorial waters. Fishermen are drawn to the greater profits that come with illegal fishing. As seen originally in Somalia, illegal fishing also damages local communities and ecosystems, forcing locals into pirate ranks to earn thousands more than they would by toiling in waters already excessively fished. Illegal fishing costs local governments an estimated 1.5 billion dollars annually.

Political uncertainty also causes piracy. Election periods consistently see spikes in violence and terrorist activities as officials feel uneasy about the fragile government systems they are a part of and, in turn, resort to orchestrating attacks on their opponents. As well as political rivalry, piracy is heightened during the transition of a regime change as pirate leaders attempt to display their power in order to gain the support of a new local elite. The uncertainty of future policy under a new regime also means pirates must strike before a potentially less tolerant leader makes piracy less viable.

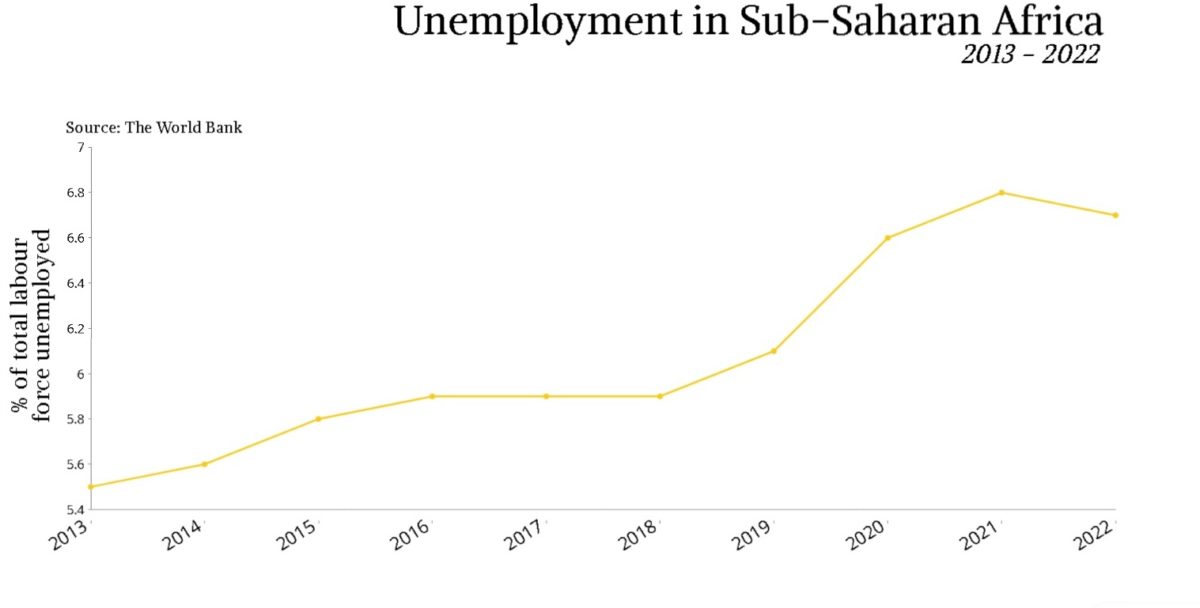

Perhaps the most difficult factor to counter is the unemployment prevalent in Western Africa, with its population of 400 million outpacing any job opportunities. An unemployment rate of 6.8 percent, according to a Statista report, which is particularly weighted toward the younger demographic, means young men continue to join pirate ranks. A lack of development is again the underlying issue here. A low number of jobs and a low yield when employed in the legal economy, while thousands can be made illegally fishing or in pirate attacks, means that piracy attempts will prevail no matter the risks these young men face. There is an essential need to decrease incentives rather than solely counter the pirates who have already taken up the cause.

Unemployment rate in Sub-Saharan Africa from 2013 – 2022.

An International Precedent: Somalia

Somalia was once infamously the hotbed of piracy in the world. However, piracy is virtually extinct in both the Gulf of Aden and just off the Horn of Africa today. An international precedent of zero tolerance has been set, so why hasn’t piracy been tackled in the Gulf of Guinea to the same absolute degree, and how was it accomplished around Somalia?

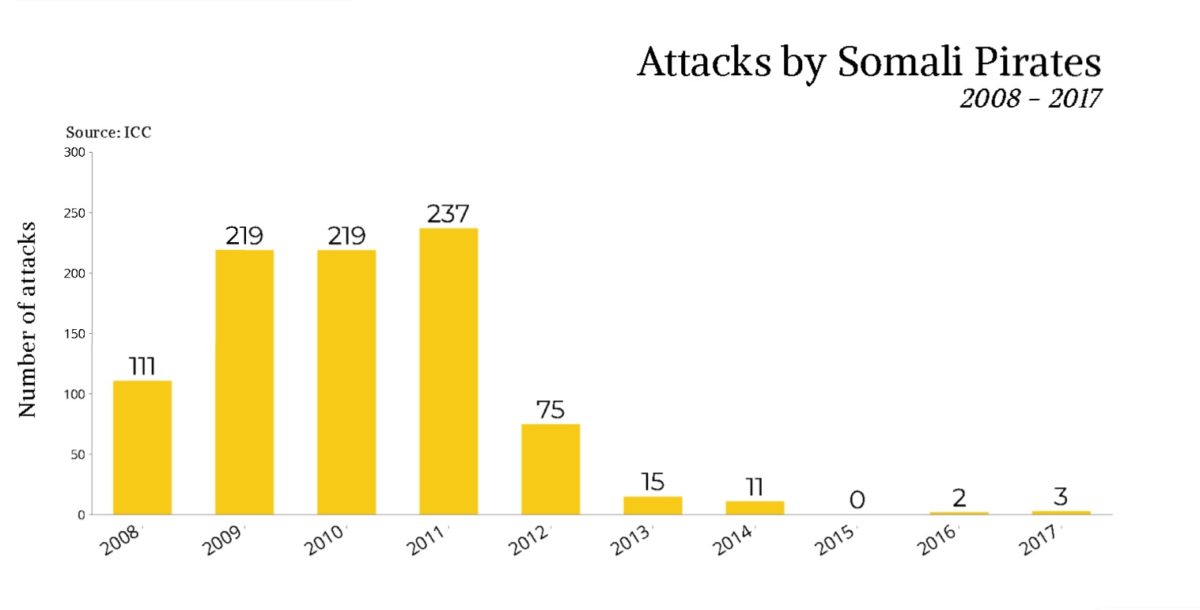

In 2011, 160 incidents were recorded, and in the five-year period between 2010 and 2015, the total tally rose to a staggering 358. However, between 2016 and 2021, these numbers fell drastically, and although the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre continues to urge shipmasters to practice caution, especially close to the Somali coast, attacks have become extremely rare.

In 2018, there were only two instances of piracy, and in 2021, there was only one, which took place in the Gulf of Aden. Even as early as 2013, the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence reported only nine vessel attacks for the entire year, none of which resulted in successful hijackings due to the countermeasures taken. An important and often understated element of counter-piracy is not just preventing attempts but reducing the chance of a successful hijacking; two of the attacks in the Gulf of Guinea this year alone have resulted in hijackings as crews are not as well equipped to repel such attackers.

The rapid decline of Somali pirate attacks from 2008 – 2017.

The ability to resist pirates during an attack was one of the issues addressed around Somalia as mandatory practices were implemented on vessels. One of these practices was equipping crews with security to counter pirates during any attack. As well as this, there was a development of onshore security forces and an increase in naval presence.

Huge international cooperation between European, American, Chinese, and Indian forces was the most important element in ending piracy in Somali waters. The lack of priority on the international agenda compared to the Somali pirate crisis is likely one of the reasons the Gulf of Guinea has not seen the same success. In 2010, the Somali government built a naval base in the town of Bandar Siyada to force pirate activity away from the coast. In 2012, an African Union mission in Somalia by Kenyan troops captured the Kismayo port from Al-Shabaab terrorists, again reducing pirate activity. By 2017, China had built a military base in Djibouti, north of Somalia to counter pirates.

A far more controversial deterrent that took place in May 2010 was when the trials of twelve pirates took place in Yemen after a Yemeni oil tanker was hijacked. Six of the Somali pirates were sentenced to death because two crew members were killed and four others were wounded in the attack. These individual efforts as well as the priority put on the issue by the international community crushed piracy in the area, and the same efforts need to be applied in the Western African seas to recreate the success.

In Summary

There is still a long road ahead for the Gulf of Guinea, and attacks will likely persist if underlying issues in the nations surrounding the Gulf are not addressed or more stringent countermeasures are not implemented. Partially drawing inspiration from the successful measures taken to curb piracy in Somalia in the past, it is crucial to prioritize the issue, implement mandatory security measures, and address the root causes to effectively mitigate piracy activities. Only through these concerted efforts can the vital maritime trade in the Gulf of Guinea be safeguarded. Progress made over the past two years, mainly due to Nigeria’s Deep Blue Project, is encouraging; however, the presence of piracy clearly persists in the Gulf and must be addressed.

Related Posts

U.S gives equipment to Nigerian Navy to combat..

The US government has handed over maritime equipment to the Nigerian Navy to secure maritime..

Don lists threats against NIMASA’s $195m Deep..

A Senior Lecturer at the Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria, Freedom Onuoha,..

IMO Urges Action to Combat Piracy in Gulf of..

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) will convene a maritime security working group in..