Recent missile attacks in the Red Sea underscore the vulnerability of commercial shipping routes, emphasising how geopolitical tensions can override commercial interests.

Unlike previous threats like Somali piracy, which could be mitigated with armed security, the more sophisticated risks posed by Iran-backed Houthi forces demand significant naval assets. This shift illustrates the broader challenge posed by critical maritime choke points that could be exploited by hostile actors.

Key shipping routes such as the Suez Canal, Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and Strait of Hormuz are particularly vulnerable. The Suez Canal, a crucial artery connecting Europe and Asia, has been a strategic chokepoint since its opening in 1869. While it significantly reduces shipping time, it remains susceptible to disruptions, as demonstrated during the Suez Crisis of 1956 and the more recent 2021 blockage by a stranded container ship. The Bab el-Mandeb, separating the Arabian Peninsula from Africa, has been targeted by both Somali pirates and Houthi terrorists. Similarly, the Strait of Hormuz, the primary passage for tankers from the Persian Gulf, remains a focal point of tensions between Iran and the West. Any disruption to this route could cause a global energy crisis, potentially triggering armed conflict.

Further east, China faces a similar challenge at the Strait of Malacca, through which 80% of its oil imports flow. A U.S. naval blockade of this strait would severely impact China’s energy supply, heightening geopolitical tensions.

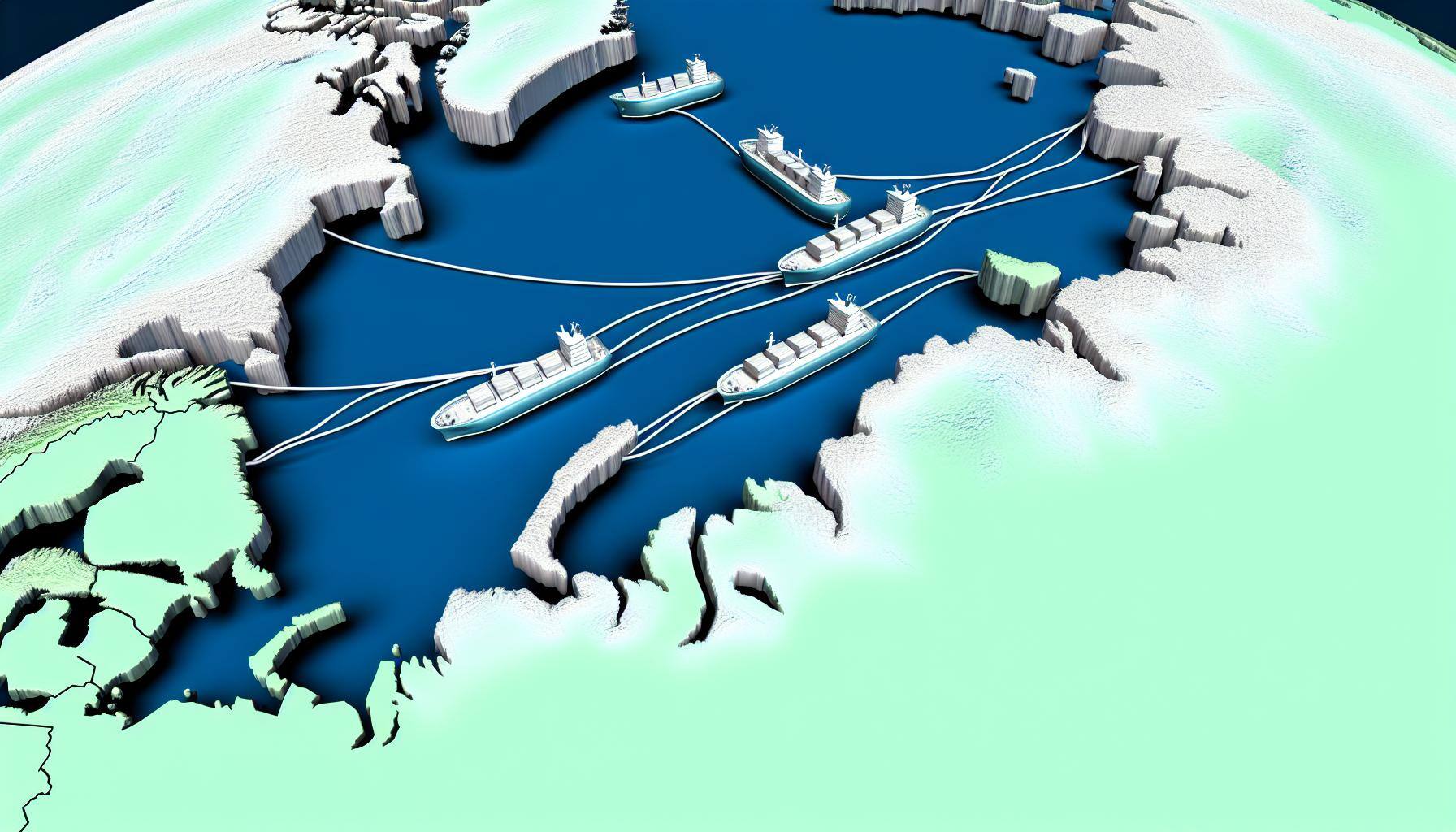

In response to the growing instability of these traditional shipping routes, attention has turned to the Northern Sea Route (NSR), an Arctic passage linking Europe and Asia. While once impassable due to thick sea ice, climate change has opened this route for longer periods, reducing the shipping distance between Rotterdam and Yokohama by nearly half. Despite the logistical advantages, the route’s commercial potential has been clouded by geopolitical factors, particularly the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russia, with significant investments in Arctic infrastructure, has been a key proponent of the NSR. Before its conflict with Ukraine, Russia and China were collaborating on expanding Arctic shipping, with both nations building icebreakers and reinforced cargo vessels. Russia’s ambitions include increasing cargo traffic from 36 million metric tons in 2023 to 240 million by 2035. However, Western sanctions in response to the Ukraine invasion have curtailed international interest in the NSR, forcing Russia to rely on domestic and non-Western partners like China and India.

The war in Ukraine has also led to the rise of a “shadow fleet” of aging, uninsured tankers operated by unknown entities, often flouting maritime regulations. These ships, used to transport Russian oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG), pose significant environmental risks, particularly in the fragile Arctic ecosystem. The expansion of this fleet underscores the potential for major maritime accidents, as these vessels lack proper safety standards.

As global demand for LNG rises, Russia’s Arctic energy projects will continue to grow, deepening ties with China and India. However, this could further destabilize global maritime security, as these powers increasingly bypass established shipping norms. The rise of the shadow fleet and the intensification of Arctic shipping signal a precarious future for global trade and maritime governance.